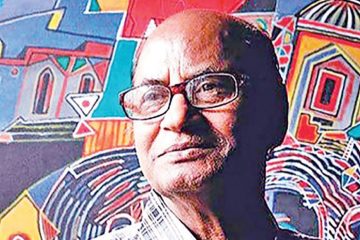

Anjan’s exhibition at National Museum

Much has been written on the glorious past of Bengali (particularly Dhaka and surrounding regions) handloom. Locally produced cotton and advanced skills of ‘taanti’ (weavers) attained worldwide acclaim in the form of ‘Muslin’ during the Mughal era. But where does Bangladeshi handloom stand now? Once known as the “Manchester of Bangladesh” for its handloom textiles, Narsingdi district is going through a very difficult phase. About 70 percent of the handloom units in the area have closed down over the last three decades, according to statistics. More and more power-looms are taking over. Despite bleak conditions, Bangladeshi handloom is striving to survive in some areas — Narsingdi being one. Devoted weavers and traders, with the support of some local fashion houses (like Aarong, Anjan’s, Aranya and Jatra) are trying to popularise hand-woven fabrics.

Much has been written on the glorious past of Bengali (particularly Dhaka and surrounding regions) handloom. Locally produced cotton and advanced skills of ‘taanti’ (weavers) attained worldwide acclaim in the form of ‘Muslin’ during the Mughal era. But where does Bangladeshi handloom stand now? Once known as the “Manchester of Bangladesh” for its handloom textiles, Narsingdi district is going through a very difficult phase. About 70 percent of the handloom units in the area have closed down over the last three decades, according to statistics. More and more power-looms are taking over. Despite bleak conditions, Bangladeshi handloom is striving to survive in some areas — Narsingdi being one. Devoted weavers and traders, with the support of some local fashion houses (like Aarong, Anjan’s, Aranya and Jatra) are trying to popularise hand-woven fabrics.

To generate interest in the handloom industry and inform on the production process, Anjan’s is holding an exhibition, titled “Sound of Weaving” (concept and suggestions by Chandra Shekhar Saha and Habibur Rahman) at the Nalinikanto Bhattashali gallery, National Museum.

The exhibition traces the initiation of handloom in Narsingdi region. Supposedly, use of ‘thak-thaki’ (named so for the sound it produces) looms and ‘charka’ (spinning wheel) in the area started in pre-Mughal/ Mughal era. The Jogi community (who were later known as ‘Nath’) became skilled weavers during the era. Weaver villages grew in the ‘char’ (river shoals) on the Old Brahmaputra. Horizontal ground looms evolved into pit looms. Handloom factories emerged subsequently in areas like Madhabdi. In the 1600s ‘Aaranga,’ a port on the Old Brahmaputra River, became a major trade centre — exclusively boosting the local handloom industry. Flows of the Old Brahmaputra have withered, taking Aaranga into oblivion.

Comparative study reveals the current state of handloom industry in the region. Handloom units in different areas have drastically diminished. Cases in point:

Meherpara: 5,000 units (before)-150 units (now)

Radhanagar: 2,000 units (before)-100 units (now)

Anandi: 300 units (before)-none (now)

Mesekandi: 1,000 units (before)-none (now)

Nilakhya: 4,000 units (before)-300 (now)

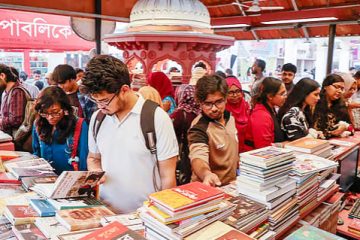

Four handlooms have been set up at the centre of the gallery. Seasoned weavers are at work. Yarn processing, which includes shedding, picking, battening and taking-up operations, is also on display. Curious visitors, closely observing the process, were seen making queries. The exhibition, seemingly, has attained its objective.

Mostly, cotton fabrics are on display. Some plain and some carefully adorned rolls of fabrics with indigenous motifs — in vibrant crimson, regal purple, lush green and more hues — are suspended from the ceiling.

Anjan’s has also honoured three individuals on the occasion. Swahadeb Bishwas (of Tatakanda village, Narsingdi) has been honoured for his dogged determination. Threatened with rising prices of raw materials, aggression of power-looms and hardship day in day out, Bishwas’ lone pit loom is still on.

Mohammad Sirajuddin has been recognised for his mastery over the Jacquard loom (used in manufacturing fabrics with complex patterns). Locally knows as the “design master,” Sirajuddin has been working tirelessly in Narsingdi and Pabna for over 70 years to develop motifs and patterns used in hand-woven fabric.

Mohammad Zahirul Haque has been lauded for his innovative ideas and endeavours to popularise handloom. In 1992 he started with renting two handlooms at his village Amdia. In the last 17 years, Haque hasn’t given in to the lure of power-looms. His passion for handloom continues, as he develops new designs and patterns.

The exhibition (ending on June 16) can be an eye-opener to many. More such initiatives are necessary to reinstate the dwindling handloom industry in Bangladesh.