Mostafa Yousuf

As if it wasn’t hard enough for elephants to survive in this country, in a tragic development, it was discovered that they are not just dying by electrocution. Shooting down the animals straight up has become seemingly rampant to protect encroached forest lands.

As if it wasn’t hard enough for elephants to survive in this country, in a tragic development, it was discovered that they are not just dying by electrocution. Shooting down the animals straight up has become seemingly rampant to protect encroached forest lands.

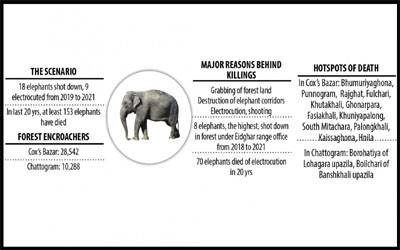

In Cox’s Bazar, 18 elephants were shot down in the span of three years, from 2019 to 2021. The Daily Star found this grim picture after piecing together the three years’ data. During this time, nine elephants were also killed by electrocution.

In the last 20 years, at least 153 elephants have died in the country, according to forest department’s data and records by this newspaper. Experts say that forest encroachers’ adoption of this lethal technique threatens to wipe out the gentle giants across the Cox’s Bazar and Chattogram ranges within a generation.

Elephants were categorised as critically endangered by International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) two decades ago, when its population in the country was assumed to be around 400.

By 2016, the number came down to just 268, according to IUCN’s last study.

The situation is particularly worrisome for Cox’s Bazar and Chattogram ranges, where half of the country’s elephant species live.

In these regions, power lines running through forests to power forest-adjacent villages as well as electric fences set up using these lines have led to the demise of numerous elephants, all to protect forest land that grabbers have encroached for agricultural purposes.

Cox’s Bazar alone has a total of 28,542 forest encroachers, while Chattogram has 10,288, according to the department’s list of land grabbers.

Cox’s Bazar alone has a total of 28,542 forest encroachers, while Chattogram has 10,288, according to the department’s list of land grabbers.

Mohammad Abdul Aziz, professor of Jahangirnagar University’s zoology department and member of Asian Elephant Specialist Group of South Asia, said lower-level officials are helpless in protecting elephants from the threat of forest grabbers. “Freeing the forest from grabbers, eliminating power lines running through the

forest and stopping agricultural activities on encroached land require strong action from high-ups of the department. Without a sincere aim to conserve elephants, all efforts will fall flat.”

In 2019, the forest department formed a four-member committee to investigate dead elephants found lying on paddy fields belonging to villagers, known as forest villagers, along the corridors of Cox’s Bazar, which are used by elephant herds.

The committee found that many of the villagers were found killing elephants and encroaching the forest. As a solution, the committee recommended freeing the forest’s corridors from these grabbers.

The “forest villagers system” was introduced in 1930. Villagers were supposed to help forest officials protect the greeneries and enjoy a minimum of 25 and maximum of 200 decimals of forest land in exchange for their cooperation.

But over the years, the protectors became detractors themselves, as the original forest villagers’ progeny are the ones who are behind the rampant land-grabbing at the forests, found the committee.

The committee’s chief, Jahir Uddin Akon, director (wildlife crime control unit) of the forest department, said, “We found three main reasons behind the elephant killings: grabbing, destruction of corridors, and electrocution.”

This correspondent took a trip to the forest of Chakaria’s Punnogram, Lohagara upazila’s Borohatiya and Jongol Sharaf Bhata in December last year to see the situation first-hand.

Power lines were seen aplenty in Punnogram forest, with one found running behind the Punnogram forest beat office. Inside the forest, there were thousands of acres of paddy field. A dozen of illegal brick kilns are also being operated within the periphery of the reserve forest.

The power lines come as a boon for grabbers, as they easily set up electric fences using galvanised wire to kill elephants.

Meanwhile, various fish farms and betel leaf gardens dominate Teknaf and Ukhiya forest, where a significant number of elephants live. In Boalkhali and Rangunia under Chattogram Forest Division (south), lemon garden and brick kilns were established throughout the elephant habitat.

Involvement of politically connected people were found behind all the encroachments.

Contacted, Molla Rezaul Karim, conservator of forest (wildlife and nature conservation), said they were seeking a gazette to secure 12 elephant corridors, proposing a project to conserve the flagship species.

“We also proposed to the relevant authorities the idea of forming a divisional elephant conservation committee and wrote a letter to the power division to eliminate power lines through the forest,” he said.