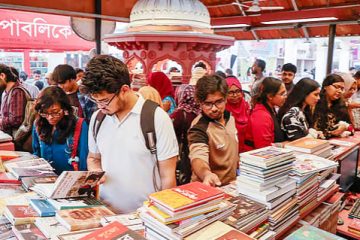

As I entered the new red brick Chhayanaut Sangskriti Bhaban in Dhanmondi, I was struck by its magnificence. The structure had remained true to the school’s founding philosophy of “open door for all”— the building purposefully has no perimeter walls. There was a constant mass of students, teachers, poets, artists, young and old streaming through the doors from dawn to dusk.

As I entered the new red brick Chhayanaut Sangskriti Bhaban in Dhanmondi, I was struck by its magnificence. The structure had remained true to the school’s founding philosophy of “open door for all”— the building purposefully has no perimeter walls. There was a constant mass of students, teachers, poets, artists, young and old streaming through the doors from dawn to dusk.

The classes for children with special needs and Nalonda, now in its 10th year, were closed in the evening, but the rest of the building was throbbing with activity. The halls were reverberating with choruses of classical, Nazrul, Tagore and folk. In between the words I could hear the strumming of the sitars and melodic violin accompanied by the deep and rapid beat of the tabla and pakhwaj. Other students were milling about, sipping tea in the cafeteria, passionately debating something or the other or just browsing through the library upstairs.

A wave of nostalgia swept over me as I remembered my student days. Chhayanaut had turned 50, and I was here to meet the person who had been one of the principal driving forces behind it — Dr. Sanjida Khatun.

She was waiting for me at her first floor office. As President of Chhayanaut, she was busy directing the last details of the programme the school had chalked out to mark the occasion to be held on November 25 and 26.

“Chhayanaut has always maintained a low profile, as we believe in work and not grandiose ideas for celebrations,” she said. “You must remember that from your student days here.”

After a few moments, a nostalgic Sanjida apa (as she is fondly known), started talking about Chhayanaut.

She recalled how Chhayanaut started. It was winter and the erstwhile Pakistan government had intensified its attempts to stamp out Bengali identity and culture from East Pakistan. A group of energetic activists, angered by the military regime’s latest tactics, decided to unite and defy the junta. To register their protest, they celebrated Rabindranath Tagore’s birth centenary in May 1961, a radical step in those times, since there was a strict ban on Tagore, she went on.

After the successful celebration, the group reunited at a picnic in Joydebpur and contemplated continuing the movement. Members of this group included iconic figures such as Sufia Kamal, Mokhlesur Rahman Sidhu, Shamsunnahar Rahman, Ahmedur Rahman, Mizanur Rahman, Saifuddin Ahmed, Saidul Hasan, Farida Hasan, Waheedul Haq and, of course, Sanjida Khatun.

It is no surprise that such like-minded cultural activists found the regime stifling and they chose to fight it on the frontier they knew best: the cultural front. With poet Sufia Kamal at the helm, the group set in motion a silent but powerful cultural revolution. Chhayanaut was thus born.

Chhayanaut signifies the shade of a tree. It was aptly named by the couple Saidul Hasan and Farida Hasan to represent an organisation under whose shade Bengali culture could be nourished and nurtured. The task of building the organisation fell upon Waheedul Huque, added a nostalgic Sanjida Khatun. He took on the role to promote all genres of music — from classical, Nazrul Sangeet, Rabindra Sangeet to folk — in their purest forms.

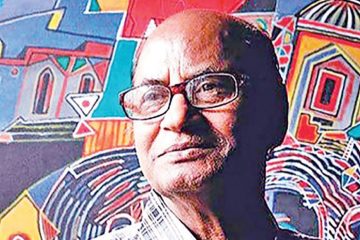

“Chhayanaut has been blessed by a core group from its embryonic stage: Saira Mohiuddin (its first vice president), Ahmedur Rahman, Saifuddowla, Dr. Sarwar Ali, Jamil Chowdury, Mazharul Islam, Hosne Ara Islam, Hosne Ara, Dr. Noorun Nahar Fyzennessa, Quamrul Hassan, Rashid Chowdhury, Debdas Chakravarti, and Nitun Kundu, to name a few. Noted painter Qayyum Chowdhury designed the insignia for Chhayanaut.

“Over the years, Chhayanaut was passionately led by a dedicated group of people such as Farida Hassan, Kamal Lohani, Ziauddin, Zahedur Rahim, Saifuddowla, Iffat Ara Dewan and currently Khairul Anam, who has been serving as its general secretary for last the 20 years. Some of the most critical pillars for Chhayanaut have been the teachers who spent their lifetime training aspiring artistes. Chhayanaut would not be what it is today if it were not for mentors such as Ustad Moti Miah, Sheikh Luthfur Rahman, Sohrab Hossain, Zahedur Rahim, Anjali Rai, Ustad Phul Mohammad, Ustad Khurshid Khan, Ustad Modon Gopal Das, Md. Shahjahan and more.

“Artistes, littérateurs, painters and, most importantly, people from all sections sought beauty in melody, rhythm, art, Bangaliana and in their everyday life. This became the driving force of our organisation,” said Sanjida Khatun with pride. Under its shade, people found a common voice and a brotherhood of cultural enthusiasts developed.

One matter of pride, said Sanjida Khatun, is that Chhayanaut grew as an inspiration for the people and was in turn, built and funded entirely by the people. However, the struggle to build a permanent home for the school went on for decades. It was only in 2005 that the school’s organisers felt they had raised sufficient funds. On a piece of land presented by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, architect Bashirul Huque designed the building’s blueprints and the school took shape.

Despite the peaceful nature of the school, it has been prone to deadly attacks. The most dreadful one was the 2001 bombing of the Pahela Baishakh programme that killed ten and injured hundreds. The Pahela Baishakh festivities had become an iconic Chhayanaut programme. People from far and wide congregated at the crack of dawn under the historic banyan tree (Botomul) at Ramna Park to listen to the top talents of the school usher in the New Year through music. It was one of the most symbolic gatherings of people who shared a common Bengali identity and an ideal target for terrorists who wanted to destroy it.

“The bomb blast threw us into a dilemma. The loss of life was extremely tragic. It also raised the question of whether we had been able to unite all sections of society in a common bond,” said Sanjida Khatun. However, the bond that people shared was truly strong. The following year, defying all expectations and fears of another attack, people in even greater numbers thronged the venue, united in defiance.

“Young minds need to be informed about their culture through any means that can best reach them. To ignite their interest, we chalked out a project ‘Shikor’ (roots) that offered classes ranging from theatre, recitation, brotochari dance to even exploring new tastes such as ‘Attkorai’. For the adults, we run a course ‘Bhashar Alap’ (language discourse).

“After the untimely demise of noted Tagore singer Zahedur Rahim, Rabindra Sangeet Shilpi Parishad was launched, which now has 75 branches all across the country. An anonymous fixed deposit donation of Taka 50 lakh funds the countrywide projects.

“Chhayanaut has grown over 50 years to be seen as the icon of traditional Bengali culture and a platform for ideas that can enlighten generations,” said Sanjida apa.

Chhayanaut, besides training minds, also tries to work for the betterment of people in times of national crises. In the ’60s when Chittagong was hit by typhoon Gorki, Chhayanaut workers organised a parade through the streets and collected funds for the victims. During the Liberation War, Chhayanaut members formed the Bangladesh Mukti Sangrami Shangstha and regularly visited the camps to lift the spirit of the freedom fighters.

Chhayanaut, true to its name, has grown from a seed into a protective tree. Under its shade it has nourished thousands of eager minds, linked millions of people and given a voice to the culture of a countless multitude. By the same virtue, the school has drawn strength from the people, channelling energy and enthusiasm into giving shape to its higher aspirations. Fifty years have gone by in the blink of an eye; one wishes that Chhayanaut leaves its mark for time eternal.

Courtesy of The Daily Star