Global Shakespeare

Dhaka Theatre stages indigenous tinged Tempest in London

John Farndon

Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” is an extraordinary play. Written at a time when Britain had barely begun to embark on its colonial age, “The Tempest” ends with the exiled Duke Prospero choosing to end his rule over the natives of some distant isle and offer them their freedom. It is this strikingly modern message of power-sharing and toleration that the Dhaka Theatre’s production of the play brings home to Shakespeare’s Globe, the reconstruction of the famous open air theatre in London where the play was first performed 401 years ago.

Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” is an extraordinary play. Written at a time when Britain had barely begun to embark on its colonial age, “The Tempest” ends with the exiled Duke Prospero choosing to end his rule over the natives of some distant isle and offer them their freedom. It is this strikingly modern message of power-sharing and toleration that the Dhaka Theatre’s production of the play brings home to Shakespeare’s Globe, the reconstruction of the famous open air theatre in London where the play was first performed 401 years ago.

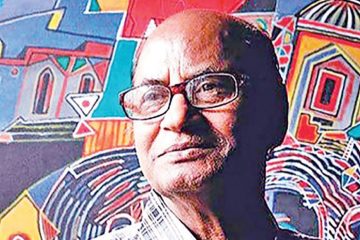

Rather than focusing on Prospero’s individual journey to understanding, acclaimed Bangladeshi director Nasiruddin Yousuff instead explores the play’s colonial themes — and in doing so underlines how both relevant and timeless Shakespeare is. At the end, tellingly, in a subtle change to Shakespeare’s original, Prospero (Rubol Noor Lodi) doesn’t simply free his native slave Caliban but hands him the conch shell that symbolises the rule of the island.

Dhaka Theatre is performing in London as part of the Globe’s remarkable season that brings 37 productions of Shakespeare’s plays to the theatre from around the world. All productions are in their own native languages and Dhaka Theatre’s production is in Bangla. Yet although the words were lost on non-Bangla speakers in the audience like myself, Yousuff innovatively blends Shakespeare with the traditional dance of the Manipuri people to create a captivating style of storytelling that transforms “The Tempest” into what seems like both an old Bengali myth and a charged political drama.

Almost a century ago, the great Bengali playwright Rabindranath Tagore created dance-dramas inspired by the Manipuri dance form. But Yousuff has done something different here. Helped by Manipuri dancers Nilmoni Singha and Bidhan Singha, he has worked long and hard with the Dhaka Theatre troupe to develop a style of performance that blends acting and dance.

The actors are not trained dancers, and some may miss the refined grace of classical dancers that takes years to develop. Instead, they are actors who move in a unique way to tell the story. The sea and sand play a central role in the imagery of this production, and the actors have, for instance, developed a light style of moving as if walking on soft sand. There is a directness and simplicity about the production’s approach that makes “The Tempest” seem both ancient and fresh — and also works remarkably well in the rude intimacy of Shakespeare’s original theatre.

Throughout the performance, the troupe squat in a semi-circle at the back of the stage, each with his or her own colourful tin suitcase of props, costumes and musical instruments. They never leave the stage, but simply get up to play their part before sitting down again — creating a continuity and a bond between audience and players that is often lost in more conventional theatre. There is a continual buzz of sound from cymbals and the dramatic pung drums, and the action is punctuated by the spectacular whirling dances of the pung drummers.

It took a while for the audience to get used to this way of storytelling, and it was only when the hugely comic trio of Caliban, Stefano and Trinculo (played by Chandan Chowdhury, Kamal Bayzed and Samiun Jahan Dola) begin their antics that the warmth between audience and performers began to develop on a cold May night in London. But once it did, the performance drew the audience in entirely, and led to a hugely enthusiastic reception in the end, as the performers returned to caper on the stage.

Underpinning it all is the haunting music created by Shimul Yousuf, who also plays Ariel with an unusually reticent presence, drifting slowly across the stage like a lost spirit, and filling the theatre with her mournful singing from behind a blue veil, as if a voice from the deep. It’s a great ensemble of highly accomplished actors, which includes Shahiduzzaman Selim as Alonso and Esha Yousuf as Miranda.

There is no great tempest in Dhaka Theatre’s production but it has the rough magic of Prospero’s enchanted island. It is, as Prospero says in the original, ‘such stuff as dreams are made on’, and carries a rightly gentle and highly relevant message for today.

The writer is an internationally known author, playwright, composer and songwriter.

Article originally published on The Daily Star