A paean to a dying art form

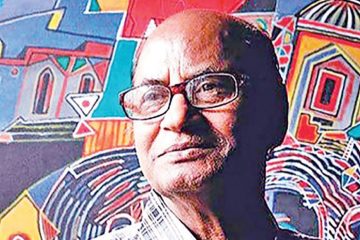

If you went down a typical alley of Dhamrai decades ago, you would have seen and heard hundreds of craftsmen and businessmen hard at work. A resounding sound came from metal being beaten to check for purity. “Before there were more than 200 workshops for mainly metal crafts of households just in Dhamrai, now there may be only 10 here and some in Savar. I used to help my uncle Shakhi Gopal Banik until he passed away and in 1993 and then I took over the business. I have about 22 young artisans working with me. This is the fifth generation of my family, in this trade beginning with my great grandfather Sarat Chandra Banik,” says Sukanta Banik, proprietor of Dhamrai Metal Crafts.

If you went down a typical alley of Dhamrai decades ago, you would have seen and heard hundreds of craftsmen and businessmen hard at work. A resounding sound came from metal being beaten to check for purity. “Before there were more than 200 workshops for mainly metal crafts of households just in Dhamrai, now there may be only 10 here and some in Savar. I used to help my uncle Shakhi Gopal Banik until he passed away and in 1993 and then I took over the business. I have about 22 young artisans working with me. This is the fifth generation of my family, in this trade beginning with my great grandfather Sarat Chandra Banik,” says Sukanta Banik, proprietor of Dhamrai Metal Crafts.

There stands a 10-headed Vishnu in the showroom. Vessels made of copper and tin, bell metal (Kasha), that serve an array of cuisine, dazzle the visitor. A traditional Indian chess set that extends to almost a metre rests at the centre of the room. It has a camel as a bishop, a castle as an elephant, a horse in its own avatar, and there is a king complete with ministers and foot soldiers. “When you move these characters, it appears to be a real battle,” says Sukanta Banik. The chess set is priced at Taka1,55,000. The ivory chess set is now in the museum.

There is a metal crafted familiar Nataraja statue of the Hindu God Shiva, the Lord of Dance. One of the brass pieces of around half metres stood out.

A statue of the wedding rituals of Shiva and Parvati stands at one corner. This is a replica of a statue kept in the Museum. There is Durga with two of her daughters, Lakshmi and Saraswati and sons Ganesh and Kartikeya killing the demon that had disguised itself as a buffalo.

Sukanta demonstrates a singing bowl. “When you are depressed and in a meditative mood, you light a candle and take the bowl. Make the shaft go round and round the bowl.”

Metal jewellery such as bangles and anklets are aplenty. Silver bangles are priced at around Taka 3,500 and brass ones at Taka 950.

Some of the metal crafts require much labour, as for instance a finely etched brass pot to store rice that took 10 months to fashion. “It is very special as it can only be made once. The craftsman has to focus on his work a great deal and it hurts his eyes over a long period. It should be given sometime before another such work is taken as it hurts the artisans eye,” adds Sukanta.

However, the future looks hazy for the metal craft business. Says Sukanta,

“Most entrepreneurs have given up the business because it seems to have no future. If the government doesn’t come forward, in the next five to 10 years, there will be no metal crafts industry left.”

Given the waning fortune of the metal craft business, it is only natural that exports of metal crafts from Dhamrai have been put on hold

All is not lost, however.

There is a possibility of this craft developing a sizeable market in North America and Western Europe and India. Some of the crafts are sold to big showrooms in Dhaka.

He is exploring other avenues as well: the documentation of the metal craft, an exhibition in Dhaka and overseas, and finally a museum at Banik Bari, the family’s 100-year-old mansion, which stands as a proud reminder of the family’s once thriving business. All these are yet dreams for Sukanta as well as for Dhamrai metal crafts.