The news of Fakir Lalon Shai’s death was first published in the newspaper Grambarta Prakashika, run by Kangal Harinath. The newspaper noted that Lalon died on October 14, 1890 at the age of 116. Based on that article, researchers point that Lalon was born in 1774. According to Bangla Calendar the day was Pahela Kartik.

The news of Fakir Lalon Shai’s death was first published in the newspaper Grambarta Prakashika, run by Kangal Harinath. The newspaper noted that Lalon died on October 14, 1890 at the age of 116. Based on that article, researchers point that Lalon was born in 1774. According to Bangla Calendar the day was Pahela Kartik.

Like many other traditional festivals and anniversaries, Lalon’s death anniversary has also been observed according to Bangla Calendar, on Pahela Kartik. There are controversies about his birthplace but it is certain that he was buried at Chheuria, where the present-day Lalon Mela is held.

Born just 17 years after the Battle of Plassey, Lalon lived over a century under British rule. Though it is not apparent how the British Raj impacted Lalon’s life and works, Lalon had a definite vision of major social reform. Apart from his mystic attributes, one of his main goals was to change a society riddled with religious bigotry.

Throughout his life, Lalon sang of a society where all religions and beliefs are in harmony.

Though Lalon is primarily identified as a mystic, philosopher, songwriter and composer, it wouldn’t be an overstatement to term him a social reformer.

During Lalon’s lifetime, undivided Bengal went through several historic events like the ‘Chirasthayi Bandobasto,’ Titumir’s Rebellion, and the Indigo Revolt. Some feel that Lalon, who didn’t receive formal education, was not aware of those social changes. But there is a question mark on this theory. It would definitely make more sense for contemporary Lalon researchers to pursue this subject rather than attempt to trace his religious background.

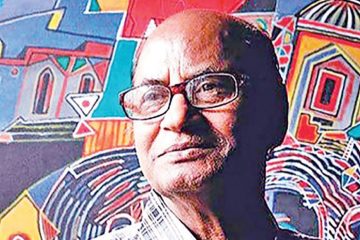

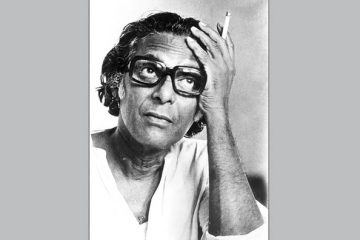

One of Lalon’s contemporary social reformers was Kangal Harinath (1833-1896). Researchers note that Lalon was a close friend of Harinath. Lalon also regularly visited the zamindar family of Shilaidah. It is said that zamindar Jyotirindranath Tagore (elder brother of Rabindranath Tagore) sketched Lalon’s portrait, which remains the only authentic document of Lalon’s visage.

Lalon’s philosophical expression, based on oral and textual traditions, was expressed in songs and musical compositions. The lyrics of his songs were explicitly meant to engage in the philosophical discourses of Bengal. He critically re-appropriated the various philosophical positions emanating from the legacies of Hindu, Jain, Buddhist and Islamic traditions, developing them into a coherent school of thought.

Lalon’s songs have attracted widespread attention for their mystical approach to humanism as well as their melodious tunes. But even after 120 years of his death, we are yet to preserve all of his songs appropriately, though the government, corporate, NGOs and many individual researchers have been taking initiatives since the 1960s.

A common problem that arises during the documentation of any orally transmitted art form from the primary source is that nobody can claim his or her work to be absolutely authentic, since words change when it is transmitted from one singer to another. Lalon Geeti is no exception to the trend. According to his followers, Fakir Maniruddin Shah, a direct disciple of Lalon, used to note down the verses.

According to the experts and true bearers of Lalon’s spirit, Lalon composed about 2,000 verses. However, many rural Bauls claim that Lalon composed over 10,000 songs. The problem is that years after Lalon’s death, many pseudo Bauls have labelled songs composed by other Baul gurus as Lalon’s.

There are different aspects of Lalon’s personality and philosophy, but it would be easier to know him through his songs. If we do so it would be a true tribute to the great mystic Baul.

Lalon proclaimed that he was beyond caste. Yet some people have persisted in confining him to a particular faith.