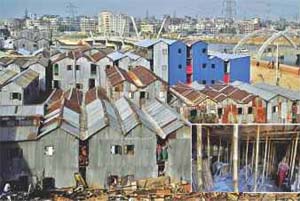

Tin Housing in Dhaka

Highly risky yet in high demand

The acrid stench of burnt metal still hangs heavy in the air on the spot where Mohammad Karim’s house once stood. It ceased to exist last Thursday, reducing Karim and a thousand others to the role of helpless bystanders as it razed swiftly to the ground, swallowed whole by billowing flames that could well have been hellfire.

The acrid stench of burnt metal still hangs heavy in the air on the spot where Mohammad Karim’s house once stood. It ceased to exist last Thursday, reducing Karim and a thousand others to the role of helpless bystanders as it razed swiftly to the ground, swallowed whole by billowing flames that could well have been hellfire.

Indeed, for Karim and many others, the judgment has been no less harsh.

“I lost everything,” says Karim.

Three little words; stark and brutal, but for Karim the consequences of losing everything are just too monumental to comprehend. He keeps repeating those three words almost continually during our brief encounter. It seems he is playing some kind of convoluted psychiatric game of repetition to help him come to terms with the loss of all his worldly possessions.

“I was going to work when I received a call from a friend saying that there was a fire,” recalls Karim, who hails from Bogra. The lean young man works for Rajuk, employed as a land measurer in the Purbachal project. “I was in Bishwa Road, when the call came,” said Karim. “By the time I reached, there was nothing to do. My home was gone,” he says, his eyes lowering to hide the welled up tears.

By any standards, home wasn’t much. Nothing more than a hastily walled-up 8 by 6 feet space, populated only in some rare cases by a proper bed. Up to six people live in each of these rooms and up to twenty rooms are littered in each of the three or four floors that make up these establishments. For the sake of comparison, most single-occupancy prison cells in the Western world are larger than that, but in Dhaka where land prices and rent are astronomically high, these rickety, dingy, uninhabitable iron-sheet houses are the sole abode for the urban poor.

Karim’s erstwhile house is in Begunbari, just a few kilometres south-west of the city’s posh Gulshan area. Most of his neighbours work either as drivers, domestic helps or peons in the numerous offices and residences just a stone’s throw away. But Begunbari is just one of many such instalments that have mushroomed up uncontrollably on the outskirts of lively commercial zones. Similar multi-storeyed iron-sheet house establishments can be found in Islambagh and in Lalbagh on the banks of the reeking Buriganga.

Even here, rent is sometimes untenable. Karim pays Tk 2,000 of his Tk 6,900 salary for his “cell”. There is no formal electricity or running water, although there is a tenuous supply of both, pilfered from nearby lines by unscrupulous owners. Natural light is a dream in the pitch-black rooms and the only way to differentiate mornings from nights are the regular screaming matches that break out like clockwork every morning about the use of water or bathrooms.

To say these establishments are a hazard would be criminally understating. Indeed, it is a wonder that such fatalistic accidents do not break out more often given the complete disregard for any semblance of safety.

Amateurishly pinned together nails and rickety bamboos serve as foundations for unsustainable vertical growth. Rotting, makeshift ladders serve as staircases as little children run amok. “The owners don’t care,” says Karim. “There is such high demand that if I leave, he will find someone to replace me in a matter of hours.”

Indeed, it seems that for the owners, it is very much a matter of just rebuilding and waiting for the influx. In the last two years alone, there have been four to five incidents of fire in these establishments. In each case, the narrative has been exactly the same a hue and cry, followed by a process of rebuilding and moving forward as if nothing had happened.

On September 23, 2010, a special feature by The Daily Star, titled “House of Horror” outlined the life inside one such structure. It spoke of how 350 people inhabited a dangerous three-storey structure, paying rent of Tk 1,200 per room.

Exactly two years on, the only things that have changed are the amplified prices of the rooms (Tk 2,000 in 2012 from Tk 1,200 in 2010) and the greater number (500 people in 2012 from 350 in 2010) of people who live in these horror houses. Such structures are illegal but there is little or no noise from the authorities who turn a blind eye while shady land-owners rake in the profits from the hapless.

But somehow, even inside these horror houses, people like Karim had found happiness. “I had everything,” he says, and now he is weeping openly. “I had some clothes, plates and a nice coloured mobile set. I had all I needed. I was happy.”

To Karim’s left are the glistening, building blocks of the new Hatirjheel project. Beyond his right shoulder, you can make out the fancy, high-rise buildings of Dhaka’s plushest zip code. But all Karim has are the clothes he is now wearing, and the vivid and painful memory of a dark, coal pit where his home once stood.

Courtesy of The Daily Star