Cat’s Macabre

Not just a play but a theatre genre

Centre for Asian Theatre’s 21st production Macabre, premiered on Tuesday at National Theatre Hall of Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, was not just a play for it could be argued that it is a theatre genre in itself.

Centre for Asian Theatre’s 21st production Macabre, premiered on Tuesday at National Theatre Hall of Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy, was not just a play for it could be argued that it is a theatre genre in itself.

It can fairly be called a ‘theatre of macabre’, like theatre of the absurd or such others. As theatre of the absurd primarily postulates the human condition as absurd, meaningless and purposeless; theatre of macabre, it can be said, posits the human condition as gruesome, grim and ghastly.

Mired in a war-tossed, bleak and barren world, the condition of humans can never be better than being macabre.

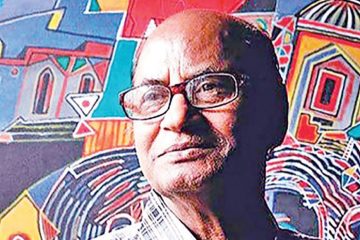

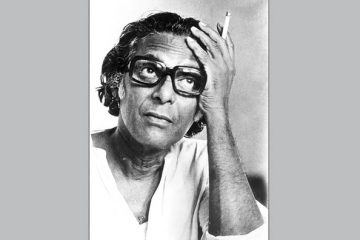

The play, scripted by Anika Mahin and directed by renowned thespian Kamaluddin Nilu, seems to deny any summarisation as there is no linear story. The play, to make a summary comment, gives vent to the ‘world as macabre’ through two prisoners’ actions and dialogues, and through abundant use of videography, music, mime and animation.

The play begins in an unconventional fashion as audiences were let in with the performers already on stage. It takes a little time for the audience to get used to the ‘macabre reality’ that the play portrays. With description, to be more precise, with question as to the identity of a corpse, the play prepares a befitting forbidding ambience right from the beginning.

Two prisoners then take the stage to tell the story, in fragments and turns, of fate, cruelty, despair and inanity of the macabre life. The unspecified and unnamed prisoners’ night-long talks equate prison to death, and shed light on the processes of how liberty dies at the hands of (un)seen and (un)revealed power structures.

In scrappy narratives, we hear the prisoners allude to the histories/ events, and we see a few numerics of years like 1971, 1975, 1976, 1981, 1990, 2006 on screens. For the local audience, it is not difficult to connect these years to their meanings, to the inseparable co-existence of death and liberty embedded in them.

What renders life and living grim and grisly, the prisoners tell, is the demand of ‘common consensus’ and the denial of individuality. And this is done in the grand names of ‘nation, nationalism and religion’, any of which acts like the one-eyed interpreter to condemn one thing and glorify others.

To force-yoke the diversities and creativities of millions of people under an umbrella is the job of nation or religion, comment the prisoners. To do so, the state needs continuous monitoring, thought-policing, torturing, manufacturing, imprisoning and others. The prisoners even enter into an animated short discussion on Orwellian concept of ‘thought-police’, which means controlling and monitoring thoughts.

It appears from the talk of the prisoners, who resemble every man in being captivated either by the concrete walls or by the walls of words, ideals and ideologies, that the only universal story is the story of domination and captivation. As the prisoners do not know where and when they were captured, they guess it might be in Tiananmen Square, in Jharkhand, in Iraq, in America, in the Caribbean or in Africa. This guess makes them unified with all the prisoners, all the dominated in the world.

The play ends with the end of the night and the prisoners’ night-long talks when they are executed. For the audience, who were bewildered into the talks, it might be a little difficult to remember the beginning words about the corpse which asks the identity of the corpse, and ask whether their eyes were shut with a kiss, whether their faces were laid on some loving laps while taking the last breath.

Macabre, as a whole, seems to be a philosophisation of the human condition in the contemporary world. Director Kamaluddin Nilu has wonderfully used the full length of the stage to make an ingenuous set, while Ahsan Reza Khan as sound, video and projection designer and Nasirul Haque as light designer did excellent.

As actors on stage Shetu Azad, Mehmud Siddique, Shipra Das, Anika Mahin, Shuvangkar Das and others were unfailing

-With New Age input