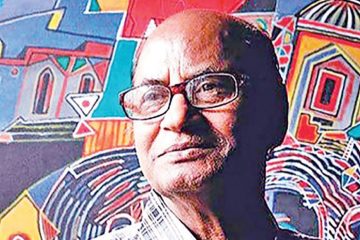

Dr Saleque Khan

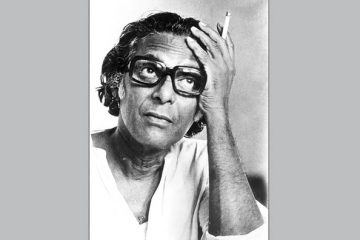

Today is the 72nd anniversary of the death of Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) a Nobel Laureate poet, philosopher, novelist, playwright, musician and painter. He is perhaps the only litterateur in the world whose songs have become the national anthems of two neighboring countries- India and Bangladesh. Tagore was also a social reformer and took initiatives such as introducing micro-credit for the welfare of the subjects under his zamindari, which now belongs to the territories of both India and Bangladesh. The nation will observe his anniversary of death today.

Today is the 72nd anniversary of the death of Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) a Nobel Laureate poet, philosopher, novelist, playwright, musician and painter. He is perhaps the only litterateur in the world whose songs have become the national anthems of two neighboring countries- India and Bangladesh. Tagore was also a social reformer and took initiatives such as introducing micro-credit for the welfare of the subjects under his zamindari, which now belongs to the territories of both India and Bangladesh. The nation will observe his anniversary of death today.

Forgive me my weariness O Lord

Should I ever lag behind

For this heart that this day trembles so

And for this pain, forgive me, forgive me, O Lord

For this weakness, forgive me O Lord,

If perchance I cast a look behind

And in the day’s heat and under the burning sun

The garland on the platter of offering wilts,

For its dull pallor, forgive me, forgive me O Lord.

Translation of a few lines from Rabindranath Tagor’s poem ‘Klanti’

WHAT would he have been had he (Rabindranath) been born in the days of Kalidasa? He asked this question to himself in his poem ‘Sekal’ (The Days of Yore). Upon dwelling on this question, I look back to find the answer both in Kalidasa, one of the nine jewels of ancient King Vikramaditya court, and Rabindranath, and the space is plays, not the entire world of works of these two great writers of India; the former is considered the master poet of Sanskrit and the latter the same in the space of Bengali language and literature.

It could probably be said that Kalidasa opens the space of apotheosis and Rabindranath brings the human in his space of work. An apotheosis by which the divine does not cease to be human, but the human develops into divine. Here comes the comparison and the question is: Upon what space Kalidasa’s and Rabindranath’s plays play upon? I find the answer is memory for Kalidasa, and the answer for Rabindranath lies in his social and political ideas.

Rabindranath’s view of man and his place in the universe is based upon his spiritual/religious belief. He believes all individuals are ultimately at one with the Absolute. And this belief produces a great respect for individuals and thus places the greatest emphasis on the freedom and dignity of the individual. He is also against regimentation and standardisation of every type and that is reflected in his plays, discussed later.

In each of his plays, Kalidasa used the hero and heroine as the main vehicles for expressing the state of his own mind. In all his plays, circumstances force the hero to leave the place of main action ignoring the embodiment of duty and emotions. The heroes of the plays are kings but their characters are expressed as sages. Therefore, they could be called royal sages. Kalidasa’s heroines are goddess-like but emotionally vulnerable. Both the heroes and heroines have dual characters to perform—human and divine.

His ‘Sakuntala and the Ring of Recollection’ could be cited as a unique example of memory play. Sakuntala, daughter of a nymph and a royal sage, lives in a hermit’s grove. When the play begins, we find that her adoptive father has gone on a pilgrimage and in his absence, Sakuntala meets king Dusyanta. This meeting leads them to a secret marriage. Sakuntala transfers her love for nature to her human lover, and she becomes pregnant. Soon after their union, the king is recalled to his capital. He leaves Sakuntala behind but gives her his signet ring as a sign of their marriage.

And the play of memory starts circling around the ring (memory as a vehicle plays a crucial role in producing romantic sentiment throughout Sanskrit literature). As the play proceeds, we see Sakuntala is distracted by her lover’s parting. She neglects to perform her religious duties in the hermitage. Sakuntala also ignores sage Durvasa, arouses his wrath, and incurs his curse. And the curse makes the king forget her, until he sees the ring again.

Eventually, the curse is broken. The king is brought to the hermitage of the divine ascetic Marica on the celestial mountain by Indra’s charioteer. This entry of the king helps him recall his first entry into the forest near Kanva’s hermitage. The local and the ambiance of this scene also have the similarity of king’s first entry in the first act, where he first met Sakuntala. In the first act, the king discovers Sakuntala in the company of her two friends in the hermitage of Kava. And again in the end, in this enchanted grove of coral trees, the king observes a hermit boy and two female ascetics. His attraction to the child grows as he suspects the child is his own son. Finally, his victory over the demons entitles him to get back Sakuntala as his wife and the child as his son who will turn the wheel of his empire. The entire play encircles the path of forgetting and remembering by producing the classical aesthetics—the rasas.

Now in contrast of memory—through parallels and cues—what Rabindranath advocates is action. In other words, he stages the scenes to move forward by breaking the present position (character assumes), space (place where things are arranged) and the past (one advocates as celestial/tradition). Examples could be cited from any of his forty over plays. But plays like ‘Raktakarobi’ (Red Oleanders: 1925), Raja (King: 1910), ‘Muktadhara’ (Free Current: 1922)and ‘Acholayatan’ (Immovable Mansion: 1912)are instant examples as these plays are well analysed and performed in both academic and performance world. I will take ‘Acholayatan’ as an example of his most potent weapon that breaks the paralysing hold on the mind of man. The attack begins when Shubhadra, a young pupil of ‘Acholayatan’, opens the window that is situated in the north side wall of ‘Acholayatan’ and sees another world outside. This news puts the pupils and the teachers of this religious school—‘Acholayatan’—in a shock. Everyone fears the wrath of goddess Ekjata. It is taught in ‘Acholayatan’ that the north side belongs to goddess Ekjata and the window should remain closed. Nobody ever thought of going outside of their mansion or having a look at the outside, only exception is Panchak—the protagonist—the disobedient pupil of ‘Acholayatan’. Upadhyya (religion teacher) bursts out into a mixed emotion of frustration and anger after hearing this news from Shubhadra (Shubhadra volunteers to tell him this news). Upadhyya cries out by saying, ‘What a disaster! What have you done! What have you done! Do you know nobody has opened that window in the past three hundred and forty-five years?’ Shubhadra asks him (in fear), ‘What will happen to me?’ Panchak embraces him and says, ‘Victory to you. You have removed the obstacle that remained there for three hundred and forty-five years.’

Removing the obstacles and moving the immovable is Rabindranath. He wants to remove the obstacles placed in the name of tradition and customs. Rabindranath logically dismisses the bigotry of established religion and calls to move forward. He could have been the tenth jewel in company of the nine jewels of the king’s court if he were born in ‘Sekal’. But he was not to be confined to the court of a king as he was destined to be muktadhara that only promises for new hope and for all.

The writer is an artistic director, actor and writer.

Article originally published on New Age