Anshuman Bhowmick

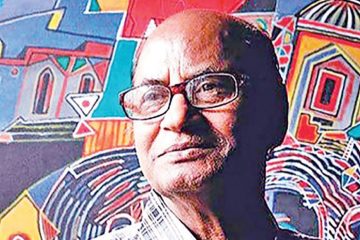

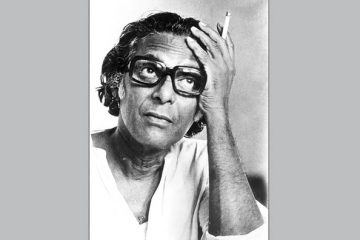

I was born two days after the passing away of Rabindranath Tagore. That was the 24th day of Sravan in the year 1348 of Bengali calendar, or 9th August, 1941, in Christian calendar,” reads the first two lines of Ramendu Majumdar’s autobiography, the English translation of which is slated for release this month. As the man turns eighty this year, his family and friends across generations and nations have reasons to feel elated. Not just because eighty is a milestone, but also because Ramendu Majumdar is special for all of them, in distinguished ways.

I was born two days after the passing away of Rabindranath Tagore. That was the 24th day of Sravan in the year 1348 of Bengali calendar, or 9th August, 1941, in Christian calendar,” reads the first two lines of Ramendu Majumdar’s autobiography, the English translation of which is slated for release this month. As the man turns eighty this year, his family and friends across generations and nations have reasons to feel elated. Not just because eighty is a milestone, but also because Ramendu Majumdar is special for all of them, in distinguished ways.

Ramendu Da, or simply Dada, as the whole of Bangladesh loves referring to him, would wake up this morning a contented man, perhaps listening to a Dwijendra Lal Roy composition sung by Luva Nahid Choudhury and sip his favourite cup of coffee. Contentment comes naturally to him. With that, comes a general sense of warmth and generosity – both his second name. One feels like using two other expressions, made immortal since Mathew Arnold used them together, ‘sweetness and light’ about Ramendu Da. We rarely come across a thoroughbred gentleman whose appearance at one end of the corridor or at a lecture podium makes one feel comfortable. He is not known for raising his voice. He is always seen smiling, a cordial gesture that transforms the colour of every assembly he attends. Add to this frame his ever-supportive wife Ferdausi Majumdar, a legendary actor in her own right, and what you receive is a pristine gift of positivity – a cure for every malady in these trying times. Conjugal bliss is not something we Bengalis are used to flaunting.

However, the Majumdars, together ever since their eyes met at the University of Dhaka, wear happiness so effortlessly that one craves for more. Seeing them together – never reminded of their different religious identities – is among the most alluring romantic escapes in a time fast grappling with the ferocious intensity of communal politics.

Born and raised in a family of legal professionals at Lakshmipur in Noakhali, Ramendu Da has seen the best of times and the worst of times, at least twice over. He has witnessed the Bengal Partition, the trauma of which never really left him. He has felt the repercussions of Noakhali riots. And of course, he has seen the emergence of Bangladesh from the clutches of cultural and military oppression. Having made his name in the advertising industry and nurtured a leading advertising agency, Ramendu Da has maintained a vigorous public life. A life dedicated – generally speaking – to the cause of Bengali culture, and Bangladesh’s theatre. I believe this singles him out among many others.

The epithet, ‘Sanskritik Byaktiktwa’, or loosely translated as a man of culture, sits so pretty on him that he does not require a hat at all. Yet, there are many feathers adorning this invisible hat. He has been a popular news reader to a generation glued to the BTV screen. In recent decades, he has carved a niche as a talk-show host. Last heard, he featured in a significant Bengali feature film awaiting a commercial release. Given his unmistakable presence in Bangladesh’s public life, a status that only kept sky-rocketing over the years, irrespective of the regimes, Ramendu Da always looks poised for positions of power, but he never hankers for any. His age-old friends at the Dhaka Club and trusted aides in the vicinity of Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy would correct me if I go wrong at this, but I have always seen authority hanging loosely about him, and this has nothing to do with power. He is someone who never boasts about his achievements as an art administrator, and loves underplaying his stellar role in shaping post-1971 Bangladeshi theatre, and projecting it internationally.

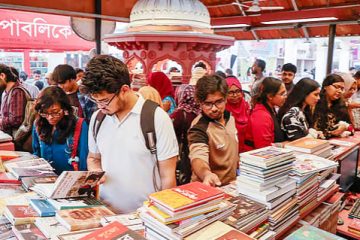

Yet, the world outside Bangladesh, my city Kolkata including, knows him as the face of Bangladeshi theatre. An avid reader, he loves coming to Kolkata at regular intervals, with the Book Fair being the major attraction. Whenever he arrives in Kolkata and settles himself in a Hindustan Park guest house that happened to be the residence of Jyoti Basu, the legendary Communist leader and a former Chief Minister of West Bengal, people from several generations come to visit him not to ask for any particular favour but simply for the joy of interacting with the man equally comfortable in a chequered lungi and beige trousers. When he visits the Academy of Fine Arts auditorium to experience a play, a general sense of reverence is palpable in the air. From octogenarians like Rudraprasad Sengupta, Bibhash Chakraborty, and Manoj Mitra, to their juniors like Bimal Chakraborty and Goutam Halder, everyone loves sharing a word with him. Many of his age love reminiscing about the past, but Ramendu Da is very much a today’s man, appreciating every expression of brilliance in contemporary theatre.

This is reflected in the pages of Theatre, a magazine he has been editing and publishing for the last five decades, a magazine that has recorded every possible register of Bangladeshi theatre as it moved ahead in time, securing a distinguished place among the nations producing plays while remaining rooted to her indigenous performance forms. His Kolkata visits entail, quite invariably, freshly printed and bound copies of Theatre, made available freely to anyone interested in Bangladeshi theatre. For many of us, Ramendu Da is Bangladeshi theatre itself.

This identity has been carried forward to distant shores. Ever since he joined the International Theatre Institute (ITI) and played the pivotal part in setting up the Bangladesh centre of ITI, his passion knew no bounds. This centre, ably supported and lapped up by his contemporaries, has given Bangladeshi theatre an international exposure, hitherto restricted to the National School of Drama, New Delhi. It is remarkable that within a decade he, along with his friend Mofidul Hoque, started editing the prestigious World of Theatre volume, and he went on to become the President of ITI, a status almost exclusively preserved by European nations and cash-rich economies till that point. He held the chair for two terms, and continues to hold the President Worldwide position – a recognition that looks tailormade for him.

Having seen him chairing a few ITI sessions in the recent past, I have reached an estimate of this man. He hogs the limelight without realising it, and never gets weary of it. He manages any crisis – often involving supremely sensitive cultural issues with diplomatic repercussions– like a self-assured referee of a football match. Thereby, one gets the ultimate Ramendu Majumdar, a referee with one foot rooted in the Lakshmipur High School grounds, and the other in any playing turf across the globe. With a whistle that hardly blows, for his authority is omnipresent, irrespective of his power.

The author is a member of the executive board in Traditional Performing Arts Forum, International Theatre Institute.

Article originally published on The Daily Star