Most of Shakespearean plays have been staged in Bangladesh by local troupes, either in pure translation or in contextual adaptation. Many of these productions are still regularly staged and some of the major Shakespearean plays are, now and then, produced in new styles and adaptations by the theatre troupes. Dhaka audiences are quite familiar with seminal Shakespeare plays like Macbeth, Hamlet, The Tempest, Romeo and Juliet, The Taming of the Shrew and others. But it is perhaps for the first time that Dhaka audience enjoyed an adaptation of The Tempest performed by tea garden workers from Habiganj who are members of Habiganj-based Protik Theatre.

Most of Shakespearean plays have been staged in Bangladesh by local troupes, either in pure translation or in contextual adaptation. Many of these productions are still regularly staged and some of the major Shakespearean plays are, now and then, produced in new styles and adaptations by the theatre troupes. Dhaka audiences are quite familiar with seminal Shakespeare plays like Macbeth, Hamlet, The Tempest, Romeo and Juliet, The Taming of the Shrew and others. But it is perhaps for the first time that Dhaka audience enjoyed an adaptation of The Tempest performed by tea garden workers from Habiganj who are members of Habiganj-based Protik Theatre.

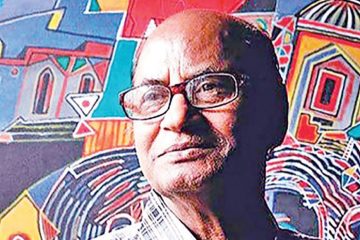

It is needless to say that a feat as out of the box as this deserves praise simply because it was attempted. But, to speak without bias, the performers did impressive, of course with some minor mistakes and inconsistencies. The plan of producing such a play came from London-based Bangladeshi expatriate theatre activist and researcher Dr Mukid Chowdhury.

Chowdhury, who is long engaged in pioneering and popularising Bengali Movement Theatre, adapted and directed The Tempest as per the tenets of movement theatre. According to this theatre form, shares Chowdhury, there is a ‘complex collaboration of performing and visual arts’ on stage. Moreover, music and dance are instrumental in movement theatre.

Be what it is in concept, the continuous dance and movements by performers while the act was being carried out by other actors could distract the audience, who is not used to movement theatre. The choreography, at times, appeared to be suggestive and symbolic of what was going on stage and at other times seemed a bit too monotonous.

Chowdhury’s adaptation of The Tempest with the name Ochin Dwiper Upakkhyan, set the play in ancient Bengal where one king is ousted by his brother, as it is in Shakespeare’s Tempest. Other happenings like the ousted king’s skilful manipulation of events and use of magic to restore his daughter to her rightful position were as it happened in Shakespeare’s Tempest. Besides, the characters, as created by Mukid, were nothing but different names with all the characteristics and dialogues of Shakespeare’s Tempest.

Tea-workers, who played different characters, seemed well-absorbed in what they were doing. It, however, should be kept in mind that their signature ways of speaking and movements, which might not be very highly polished for the urban audience, must not mar their credits.

The set was evocatively done with nets, bamboos and leaves. The use of net as a partition between corporeal and incorporeal beings’ appearances was marvelous, while leaves and bamboos suggested the isle where all the actions take place.

Not to end with the set, what comes to one’s mind after watching such a show is that theatre is nothing to be monopolised by the urban, well-off class; people from all walks of life deserve a voice.

-With New Age input