Lubna Marium

Being a lifelong Tagore aficionado, I was mildly shocked when Chhayanaut, the Bangladeshi bastion of Tagorean music, decided against allowing us the use of their auditorium, because our dance practice seemed to their authorities, to militate against Tagorean aesthetics. It set me thinking. Should there be only one interpretation of Tagore’s works?

Being a lifelong Tagore aficionado, I was mildly shocked when Chhayanaut, the Bangladeshi bastion of Tagorean music, decided against allowing us the use of their auditorium, because our dance practice seemed to their authorities, to militate against Tagorean aesthetics. It set me thinking. Should there be only one interpretation of Tagore’s works?

As Bengalis, we cannot deny that we have not done enough to take Tagore’s literature to the world. Whereas stalwarts like Shakespeare and Ibsen have been adopted, adapted and performed worldwide, Tagore continues to be, more or less, imprisoned within the confinements of the Bengali speaking community. None will disagree that the universal message of his writings needs to be disseminated far and wide. But, is that possible without letting him loose from our emotional apron strings?

But what were the poet’s own thoughts about his creative endeavours?

The quintessential traveler, both in the physical and spiritual sense all his life, Tagore searched for a universal form of art. During a conversation between Tagore and Romain Rolland, Tagore said: ‘I have always felt puzzled why there are such great differences in musical forms in different countries. Surely music should be more universal than other forms of art, for its vehicle is easy to reproduce and transmit from one country to another’ (Villeneuve, 24 June 1926)

He explains this life-long endeavour by writing in his essay, ‘The Meaning of Art’: Life is perpetually creative because it contains in itself that surplus which ever overflows the boundaries of the immediate time and space, restlessly pursuing its adventure of expression in the varied forms of self-realization.

Late in life, awed at the sight of the dance of the Manipuris, Tagore rued the fact that Bengal was deprived from the joy of dance. However, never one to sit back and bewail matters, he immediately invited dance gurus from Manipur and Kerala to Santiniketan. Thence emerged a refreshing new dance style.

Of course, as all things new, it was and still is open to debates. This debate embarks first and foremost with the degree of Tagore’s own involvement in the genesis of this style of dance. It is a well-known fact that Tagore’s daughter-in-law, Protima Devi, imbibed with an awe of balletic performances during their European tour, was enthused with a desire to present Tagore’s dramas in the dance form. Though choreographed by dance teachers under her supervision, in the memoirs of ‘Asramiks’ Amita Sen et al, we are told that no performance would go on stage without the final approval of Tagore himself. This is corroborated by Shailajaranjan Majumdar, when writing about Rabindra Nritto: ‘ Their every stance, posture, look, the modulation of their voices – elimination of the unbecoming, inclusion of which was anathema according to him (Tagore) – every step of the way the troupe was painstakingly guided and groomed by him (Tagore)’.

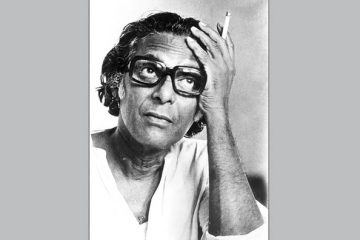

Though the style is largely based on the classical dance traditions of India, Tagore shifted from the traditional and encouraged an emphasis on the creation of the larger picture rather than an overt emphasis on detailed artistry. In fact, this remains true for Rabindra Sangeet, Tagore’s own unique songs, too. As Satyajit Ray, the renowned film-maker, remarks in ‘Thoughts on Rabindra Sangeet’: Rabindranath’s overwhelmingly individual creation in songs cannot be assigned a genre by prevailing rules because Rabindranath never thought about genres. He aimed at a distinctive specialty, at presenting certain specific feelings in specific words and specific melodies and rhythms.

Also, Tagore was open to the inclusion of any style as long as the final choreography or structure could blend in with his own ‘aesthetic’ image. During his lifetime he actively encouraged pupils to visit and learn dances from such diverse places like Kandy, Bali and Burma. Srimati Devi, a distant relative of the Tagore family is known to have presented Tagore’s lyrics in the balletic style.

Of course, Rabindra-nritya is defined by parameters which make this form of dancing distinct. Debate again arises in the defining of these very same parameters.

In various writings, Tagore has stressed on the language of art which, for him, was more indicative than descriptive, such as in the following passage in ‘Kabbo: Sposhtoebong Awsposhto’: In poetry it is often seen language does not explicitly express the spirit of the emotions, rather through suggestion it directs us towards it. Here unexpressed symbolism supersedes language. Though accuracy is generally necessary, at times like these we have no need for lucidity.

The ever-evolving dynamism of the style, which is in fact its greatest strength, has, unfortunately encountered the most criticism, due to inept interpretations. Here we have a style which is based more on a concept rather than on elaborately laid down rules and regulations. The end goal is to be able to get the message across. By tying down Tagore’s most dynamic legacy to a particular interpretation we shackle it.

As a dancer, I feel that my greatest tribute to Tagore is in experimenting with the various ways in which his timeless literature can be brought on stage for the most diverse of audiences, beyond ‘boundaries of the immediate time and space’.

The writer is a dancer, researcher and writer

Article originally published on New Age