Theatre Review

“Khona”: A legend revived!

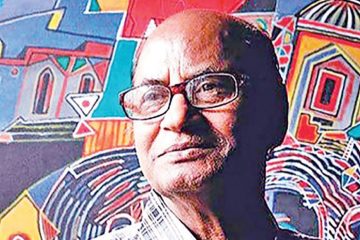

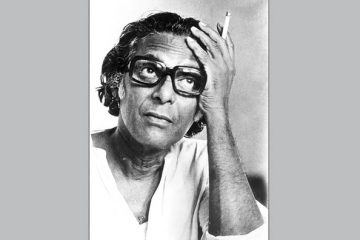

Aly Zaker

‘Bot-Tola’ is a new theatre group. Some say it is a splinter group of an established theatre company. I don’t know if it is or not. And I don’t care. It’s the quality of work that speaks for the group. Very often it has been seen that the so-called splinter group supersedes the ‘original’ in terms of artistic excellence. Our theatre arena is replete with such examples. Bot-Tola (under the banyan tree) is a familiar Bangla expression that goes beyond what it literally means. It transcends the literal meaning, and connotes… a shadow, a refuge, an assurance that gives people hope, security and, more importantly, courage. Watching the group perform at the Oxford International School, I thought that they really lived up to the connotation fully in their maiden production of “Khona.”

‘Bot-Tola’ is a new theatre group. Some say it is a splinter group of an established theatre company. I don’t know if it is or not. And I don’t care. It’s the quality of work that speaks for the group. Very often it has been seen that the so-called splinter group supersedes the ‘original’ in terms of artistic excellence. Our theatre arena is replete with such examples. Bot-Tola (under the banyan tree) is a familiar Bangla expression that goes beyond what it literally means. It transcends the literal meaning, and connotes… a shadow, a refuge, an assurance that gives people hope, security and, more importantly, courage. Watching the group perform at the Oxford International School, I thought that they really lived up to the connotation fully in their maiden production of “Khona.”

My generation grew up hearing about legends of an extremely wise and erudite woman who, through very simple expressions, could make accurate predictions about day-to-day lives. These sayings or ‘bachans’ as known in Bangla, have often been repeated by our elders whenever we were confronted by nature’s endowment or calamities. I grew out of Khona’s bachan with advancing age except when in my ancestral village or talking to fellow villagers. That there was such a fascinating myth around Khona that deserved more than a cursory interest was unknown to me until I had the opportunity to see the ‘Bot-Tola’ production of the play “Khona.” The play, written by Samina Lutfa Nitra and directed by Mohammed Ali Hyder, was a feast for the eyes and the soul. More for the soul because it brought to the fore the things we have otherwise taken for granted.

The story of Khona is shrouded in mystery, which has been interpreted through various stories by people throughout the ages. All stories centring on Khona, however, indicate that she was an astrologer just as her husband Mihir and father-in-law Varaha Mihir. As an astrologer Khona was known to be more competent than the much-vaunted father-in-law of hers. To prove that his deductions were wrong, Khona marries Varaha’s son Mihir and arrives at his hub at Deul Nagar. She tries to correct the wrong deductions by her father-in-law and earns his wrath. A conflict ensues between the father-in-law and daughter-in-law. This gets to an extreme proportion whereupon Varaha Mihir is not able to withstand the sight of his daughter-in-law. His son, a simple guy, is at a bay. Much as he loves his wife, he does not have the courage to stand against his all-powerful father.

The interpretation of the playwright is that Khona’s father-in-law felt threatened by the astrological prowess of his daughter-in-law and therefore the jealousy turned into a will to cut her down to size. Nitra, the playwright, also sees in this an archetypal male-female conflict in which the male wants to have the last word in a patriarchal society. At one point Varaha cannot take it anymore and lays a conspiracy to do away with his ‘insolent’ daughter-in-law. While watching the play, I thought that the strength of Khona was not intrinsic to her astrological knowledge but her will to learn from the experiences of the common farmers and artisans of the society in those days. Therefore, whatever the interpretation, we see the playwright highlighting the aspects of relationship between Khona and the common people transcending their respective class character and her total devotion to knowledge. Indeed in one of the most important dialogues of this play she says in as many words that knowledge was above all. Knowledge ruled over emotion, relationship and all other worldly possessions.

Through this play we are reminded of the age-old sayings of Khona. Sayings such as “If it rains at the end of the month of Magh, the harvest promises affluence for the ruler” or “If it rains at the end of Falgun, one could bring home twice the yield” or “Do not cut banana leaves after planting of the saplings and that would ensure your food and clothing.” At the end of the play Khona defies the dictates of her father-in-law and disregards the King’s request to apologise to Varaha. Surrounded by the peasants of the village, she allows her tongue to be severed by the orders of Varaha Mihir. Her last message to her followers is that “knowledge is truth.” This keeps ringing in our ears amidst the chanting of her followers, who seem to swell beyond the paltry numbers present on the stage to millions spread all over the world.

Khona, needless to say, is one of the finest plays that I have seen in years on the stages of Dhaka. The script was simply fantastic. Samina Lutfa Nitra, playing the protagonist, emerges to be one of the best actors of the day and was deftly supported by a band of dedicated actors, musicians and crew. The choreography was nearly perfect. The director, Ali Haider, did a good job though he could have checked the temptation of wanton gimmicks and the play would have been even more powerful. Hat’s off to ‘Bot-Tola’!

The writer is a renowned actor and director.