Can a quadriplegic woman be a good parent? Her ex-boyfriend filed a custody suit that says no.

From Chicago Tribune

Kaney O’Neill knows she has limits as a mother.

Kaney O’Neill knows she has limits as a mother.

The 31-year-old Des Plaines woman cannot walk, move her fingers independently or feel anything from the chest down. A decade ago, O’Neill was a Navy airman apprentice when she was knocked from a balcony during Hurricane Floyd, leaving her a quadriplegic.

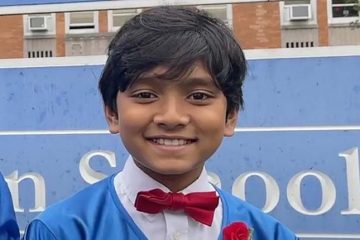

When she discovered she was pregnant last December, she felt fear and joy, a journey the Tribune chronicled in August. She quickly embraced the opportunity to raise a child, feeling she had the money and family support to make up for her paralysis. David Trais, her ex-boyfriend and the 49-year-old father of their now 5-month-old son, disagreed that she was up to the challenge.

In September, Trais sued O’Neill for full custody, charging that his former girlfriend is “not a fit and proper person” to care for their son, Aidan James O’Neill.

In court documents, Trais said O’Neill’s disability “greatly limits her ability to care for the minor, or even wake up if the minor is distressed.”

O’Neill counters that she always has another able-bodied adult on hand for Aidan — be it her full-time caretaker, live-in brother or her mother. Even before she gave birth to Aidan, O’Neill said, she never went more than a few hours by herself.

The custody case, expected back before Cook County Judge Patricia Logue next month, raises profound questions about what rights disabled parents have to care for their own children.

Ella Callow, the director of legal programs for the National Center for Parents with Disabilities and their Families, said disabled parents are incorrectly “perceived as unable to perform to standard.”

“No judge wants to be the judge who sends a child home when the child gets hurt,” said Callow, of the Berkeley, Calif.-based advocacy group.

Callow said the bias against disabled parents is such that judges tend to grant custody to an able-bodied partner “even if they have a history that might usually be a heavy mark against them — not having been in the child’s life, a history of violence, etc.”

Trais declined to comment to the Tribune when reached by phone. His attorney did not return repeated calls for comment.

But Howard LeVine, a Tinley Park attorney not affiliated with the case, said Trais’ concerns are legitimate and may hold legal weight.

“Certainly, I sympathize with the mom, but assuming both parties are equal (in other respects), isn’t the child obviously better off with the father?”

LeVine, who has specialized in divorce and custody cases for the last 40 years, pointed out that O’Neill would likely not be able to teach her son to write, paint or play ball. “What’s the effect on the child — feeling sorry for the mother and becoming the parent?”

On a recent morning, O’Neill’s caretaker, Sasha Davidiuk, propped Aidan on a pillow in O’Neill’s lap and O’Neill held her son. She has full use of her biceps muscles.

When his bottle fell from his mouth, or tipped the wrong way, Davidiuk stepped in to reposition it.

The two worked in tandem, with Davidiuk heading up duties that require manual dexterity — like changing diapers — and O’Neill focused more on emotional engagement. When Aidan burst into tears, for example, O’Neill was the one to sooth him with a soft rendition of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”

In addition to Davidiuk, O’Neill’s brother, an ex-Marine, lives in an apartment attached to her home. O’Neill’s mother helps on weekends and the family keeps Pele, a yellow lab service dog, who can open doors, turn on lights and pick up stuffed animals.

Her immaculate, one-story home is filled with photos of Aidan. Her son’s room, painted sherbet green and decorated with cheerful zoo animals, has a specially modified changing table and crib that allows for O’Neill’s wheelchair.

In an overflowing folder marked “Mommy vs. Daddy,” O’Neill keeps a copy of legal filings, tax records and proof of her income, including statements that reflect she receives $91,000 a year in veteran’s benefits that pay for her care. She also owns a general contracting company targeting federal government contracts earmarked for businesses owned by disabled veterans. O’Neill said the company, a 2-year-old startup, has not yet generated a profit.

How the Cook County case will play out is impossible to predict, say legal experts, who point out that O’Neill’s disability, in and of itself, cannot be the determining factor.

“You cannot categorically discriminate against people because of their disabilities,” said Bruce Boyer, director of the Civitas ChildLaw Clinic at Loyola University Chicago School of Law, referring to one of the central tenets of the Americans with Disabilities Act. “You can consider the ways in which someone’s circumstances might interfere with a person’s ability to have the child’s needs met.”

Helene Shapo, a professor at Northwestern University’s School of Law, said such custody fights often come down to a judge determining “the best interests of the child — a very nebulous standard that the courts use.”

Shapo pointed to a 1979 landmark case in which the California Supreme Court reversed lower court rulings against a paralyzed father who had been fighting to retain custody of his two children. In its opinion, the court found that the “essence of parenting is not to be found in the harried rounds of daily carpooling” but rather “in the ethical, emotional and intellectual guidance the parent gives the child throughout his formative years.”

As is common in child custody battles, the plaintiff did not limit his legal complaint to one concern.

Trais, a self-employed Chicago attorney, also charged in legal documents that O’Neill suffers from depression and that she smokes cigarettes and drinks alcohol in front of the infant.

O’Neill said she sees a therapist once a week and has been treated for anxiety, depression and sleep apnea. She denied Trais’ claim she smokes or drinks — though both are legal practices.

“Who is lighting my cigarettes and pouring my drinks?” she quipped.

Despite the acrimonious nature of their current relationship, O’Neill said she is committed to keeping Trais in their son’s life. She said she was devastated when she learned Trais had deemed her “unfit” in court papers and said she believes it was motivated by her decision to break up with him shortly after Aidan’s birth.

Trais currently has visitation rights from 4 to 7:30 p.m. Mondays and Wednesdays, and overnight on Fridays, according to O’Neill.

To be sure, O’Neill is not the first mother to parent from a wheelchair.

Marca Bristo, president of Access Living, a Chicago community center providing advocacy and direct service for people with disabilities, was 23 when she suffered a spinal injury in a 1977 diving accident that left her paralyzed. She gave birth and raised two children when she was in her 30s.

“I won’t kid you, it’s harder to be a mom with a disability,” Bristo said. She said both she and her kids learned to adapt. As her children got older, and starting to walk, verbal cues became increasingly important.

“You develop different voices” for warning children, since physical intervention isn’t an option, she said. “My kids knew that ‘danger voice.’ They would stop in their trails when they heard that voice.

“My kids did fine.”