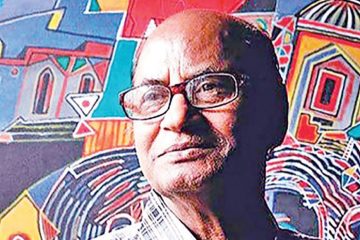

In conversation with Lubna Marium

Lubna Marium — aesthete, danseuse, dance pioneer, teacher, choreographer and impresario is a pioneering figure in the contemporary South Asian cultural scenario. Daughter of illustrious parents Colonel Quazi Nooruzzaman and Professor Sultana Zaman, Lubna Marium has dedicated a lifetime to the promotion of culture, particularly dance and other performing arts. She is the director of Shadhona — a center for promotion of South Asian performing arts, and principal of Kalpataru — a school of dance, music and arts in Dhaka. This interview provides an insight into the fascinating mind and work of this creative personality.

Lubna Marium — aesthete, danseuse, dance pioneer, teacher, choreographer and impresario is a pioneering figure in the contemporary South Asian cultural scenario. Daughter of illustrious parents Colonel Quazi Nooruzzaman and Professor Sultana Zaman, Lubna Marium has dedicated a lifetime to the promotion of culture, particularly dance and other performing arts. She is the director of Shadhona — a center for promotion of South Asian performing arts, and principal of Kalpataru — a school of dance, music and arts in Dhaka. This interview provides an insight into the fascinating mind and work of this creative personality.

I understand you had planned to train as an architect, but somewhere you changed course. Who or what inspired you to dedicate a lifetime to the arts, particularly dance?

Lubna Marium: As a child I was a bookworm, nose dipped deep into volumes I could barely hold, and thus an introvert. Fortunately, both my parents were liberal and progressive Bengalis who wanted their children to understand and love their culture. We siblings were therefore enrolled into the dance and music classes at BAFA. Dancing gave me wings and transformed me. Subsequently the Language Movement came to us as a great cultural impetus. It made us aware of our cultural roots, helping us delve deep into our creative consciousness. Then 1971 (the Liberation War) happened, which opened up yet another horizon.

A friend of mine and I visited Kalakshetra and Kalamandalam (two pioneering centers for revival of dance and performing arts in south India) in search of dance. Those were however not times in Bangladesh when girls consciously chose to take up a career in the performing arts. Following the conventional career path, I therefore started studying architecture. However by then the dance-bug had bitten me already. So mid-way, abandoning my plans of becoming an architect, I went off to Kalakshetra to learn dance — primarily Bharatnatyam. Subsequently, there were personal problems, so I came back to Dhaka, got immersed in raising a family and earning a living. In those days there weren’t any opportunities in Dhaka and one had to go to India to train in classical dance; my dance lessons came to an abrupt end.

Although years later I once again started training in dance, this time in Manipuri with Shantibala Devi in Bangladesh, I realised I had missed the bus and it was too late to take up dancing as a career. So, I thought of ways in which young people could train in Bangladesh without having to leave home. Thus, ‘Shadhona’ was born. Alimur Rahman, our chairperson and a very inspiring individual, showed us how beautiful our classical arts are. Since then, the scope of our work has increased manifold.

One of the things that come across consistently in your works is the strong element of aesthetics. Most of the dance productions that one sees now-a-days have a lot of grandeur but lack the element of aesthetic refinement and restraint. The productions of Shadhona are noted exceptions in this regard. How did you imbibe this rather rare sensibility?

Lubna Marium: We need to understand the purpose of art, literature and music. If these are revelations of our inner consciousness, then the mediums of art are mere vehicles of expression. I feel, what we ‘need to express’ must take precedence over ‘how we express’ it. In fact the artiste too is an instrument of representation. Once we understand the fundamental purpose of art, aesthetic refinement or restraint as you call it will come naturally. For example even if you write Shakespeare in gold, it’s the words that will always matter more.

I, however, don’t think aesthetics is a rare sensibility. I think it is innate to nature and humans. Nature is near perfect. Folk art and music are simple, but beautiful. This faculty gets destroyed when the purpose of art is other than the joy of creation. Once there is genuine joy in creation, aesthetics flow naturally.

No two Shadhona productions have been similar and you have always presented something new. There’s also a sense of creativity, experimentation and innovation (introducing jazz, aerial and western contemporary dance in Bangladesh) that sets Shadhona apart. Can you tell us something about this?

Lubna Marium: I do have the ability to recognise talent and giving it its due to the maximum extent I can. Having myself, withered away opportunities in my early life, I keep urging young talented artistes to make use of their abilities and push their own boundaries.

Also, I keep myself abreast of artistic ventures the world over. Presently there is a great meeting of artistic minds and genres taking place all over the world. And, that is how it should be. The arts have to be a reflection of the times in which they were created. In dance ethnography, we learn that ‘movement’ itself is ‘cultural knowledge’. Our world has changed. We live in urban jungles, we communicate through the ether-net. Our arts too must reflect the times we are living in. Fifty years hence, connoisseurs should be able to recognise the era in which a piece of art was created. However, at the same time I am also a great admirer of tradition. If our foundation is strong, we increase our potential to branch out. South Asian arts are definitely ‘mytho-poetic’ in nature — dance with its entire language of hand-movements; the raga system expressing moods of time and season. We need to build on the strong foundation of tradition and then move on to claiming new frontiers of art.

Shadhona has done some pioneering work in reviving almost extinct dance/martial arts forms — Lathi Khela and Charya dance for example. Could you elaborate on this?

Lubna Marium: At Shadhona, we have been working on a folk-narrative, and needed movements that better express the narrative. That started me off on a search for indigenous dance forms. I was astonished to find, in Bangladesh, some beautiful performing traditions which included vibrant dance forms — Padmar Nachon, Lathikhela, Jari. We couldn’t just learn these traditions and ignore the practitioners who have nurtured and preserved them with almost no patronage. Thus the ‘Robi Cholo Lathi Kheli’ project started. Similarly, we are working on a Buddhist narrative, which incorporates the ancient “Charyapada” lyrics. Again, I went a-searching and found Charya Nritya — a Tantric dance which has its own set of hand-gestures. This led me to researching into the origins of our language of hand-movements. In fact, my interest is in the entire gamut of work dealing with the body-mind connection, on which practices like ‘yoga’ are based. Lets see where this search takes me.

Your latest institutional initiative has been Kalpataru — the centre that you have set up for teaching and learning dance, theatre and other creative arts for children. Can you tell us something about that?

Lubna Marium: I feel sad with young people putting so much importance in knowing the sciences, and giving the arts a secondary role. I get frustrated with so much resources being spent on material wealth and so little on art. I get frustrated with the millions being spent on cricket and football and so little on our own arts. But, I’m an optimist. I think human beings are far too intelligent to self-destruct this world.

I would like Kalpataru to grow into a creativity centre. An integral part of Kalpataru (at Banani, Dhaka) is ‘Mancha’ — a small auditorium that is used by students of the school, as well as other artistes for their performances. It is aimed at providing residents of Dhaka, particularly in the Gulshan-Banani-Baridhara areas, a forum to experience and enjoy performing arts. Regarding Kalpataru, I firmly believe that the arts should be an integral part of a child’s education as Tagore had said, time and again. This world is “true” and we understand its truth through science, but the world is also joyous and beautiful, and we can learn to appreciate its beauty through the practice of the arts.

Courtesy of The Daily Star