Ma Taslim

The governor of Bangladesh Bank seems to have come out of the early euphoria over the central bank’s rapidly increasing international reserves caused largely by remittances.

The governor of Bangladesh Bank seems to have come out of the early euphoria over the central bank’s rapidly increasing international reserves caused largely by remittances.

Like most other people he was convinced of the virtues of an ever-increasing flow of remittances and large reserves. But the balance sheet of his bank, and that of the rest of the financial system that he supervises, seem to have nudged him to the realisation that it is not an unmixed blessings.

In his speech to the Small States Forum 2009 at Istanbul, he hinted at the emerging macroeconomic problems caused by rising remittances.

Most economic variables have flow-on effects, some of which go beyond what was originally intended or anticipated. The toughest dilemma of macroeconomic management is that most good things happen together with some undesirable outcomes.

For example, an increase in employment (or investment) often comes at the expense of rising inflation. Remittances are no exception; they too have flow-on effects that are neither immediately apparent nor always beneficial.

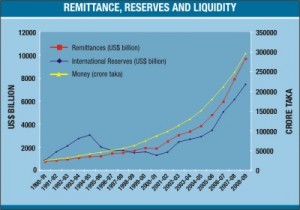

Remittances are inflows of foreign exchange into the country from our workers overseas. If the central bank does not interfere with the operations of the commercial banks then the foreign exchange received from overseas remains as foreign exchange in the balance sheets of the commercial banks. However, our central bank, Bangladesh Bank (BB), requires commercial banks to surrender most of their foreign exchange receipts to it in exchange of local money. When such a requirement is in force, any remittance shows up in the balance sheet of Bangladesh Bank as an increase in international reserves, which has immediate implications for the supply of domestic money.

This may be explained with the help of two basic monetary equations. Total high-powered money (or reserve money) is equal to domestic credit (or assets) plus international reserves held by Bangladesh Bank. The money that we use in our daily transactions derives from the quantity of high-powered money. The total supply of money is equal to money multiplier times the high-powered money.

The value of the money multiplier in Bangladesh during recent months has been about 4.3. This means that a $100 inward remittance will raise reserves by about Tk7000 ($100×Tk70/$), which will finally translate into an increase in money supply of Tk7000×4.3=Tk30100. A large increase in remittances thus translates into a correspondingly large increase in money supply or liquidity.

The central bank has instruments to prevent money supply from increasing. One of these is sterilisation, i.e. sale of credit (government bonds/bills) to the public or, what is called in BB parlance, ‘reverse repo’ operations. This allows the BB to mop up excess liquidity from the market.

The other effect of remittances is on the foreign exchange rate (in Bangladesh this usually means taka-US dollar rate). When there is a large inflow of foreign exchange, the supply of foreign exchange increases, and the value of the foreign currency tends to depreciate; or what is the same thing, the local currency, taka, appreciates.

If the central bank does not want this to happen, it has to purchase from whatever foreign currency stock the commercial banks hold. In the recent past Bangladesh Bank aggressively intervened in the foreign exchange market to mop up excess foreign currency from the market. While this shores up the demand for the foreign currency (US dollar), and hence, the value of the dollar, it also increases the reserves held by Bangladesh Bank.

It is believed that if BB had not engaged in these operations, the value of the US dollar could have fallen to the low 60s. The mayhem it could have caused to our export sector, and thereby the entire economy, is obvious. This suggests what forces the BB hands when it engages in such market interventions.

However, this is not the end of the story. The increase in international reserves increases the money supply of the economy by the money multiplier as given by the equation above. If BB had mopped up, say, one billion dollar, it would have increased reserve money by Tk 7,000 crore, and therefore added to the money supply by Tk 30,100 crore.

The BB could in theory sterilise this by engaging in reverse repo; but the fact that the governor has publicly complained about rising liquidity is an indication that the central bank is fast approaching the limits of its use. The economy is probably not able to absorb more government bonds/bills at the existing terms and conditions.

Fortunately for the country the rising liquidity has not shown up in rising inflation mainly because of the current recession. Commercial banks are unable to lend the excess liquidity since investment demand has dried up and import costs have fallen. The growth rate of private credit has fallen precipitously from 24.9 percent to 14.6 percent. This has significantly dampened aggregate demand of the economy, which put a lid on the prices (as well as on growth).

When the world economy emerges out of the current recessionary spell, the domestic economy is expected to pick up momentum. If remittances maintain their bullish tendency and the government implements its promised infrastructure and other projects, the major problem will be managing aggregate demand. A large increase in demand will most likely stoke the fire of inflation. The current lull is the right time to prepare for the contingent outcomes.

Professor MA Taslim is currently the CEO of Bangladesh Foreign Trade Institute.