Brendan Weston

The city’s traffic has grown increasingly crowded and chaotic for more than a decade, and is a disaster even by the standards of less developed countries (LDCs). Productivity is suffering, as workers with once-short commuting distances now make glacial progress in gridlocked daytime traffic that averages barely five miles an hour. Crowded into dilapidated, steamy, fume-belching private buses, they arrive to work tired, perspiring, short of breath and tainted by dust. Those with cars inch along, tapping their horns their cell phone out and A/C blasting, getting atrocious fuel efficiency. Three-wheeled taxis sometimes jump ahead, but the breezes are short-lived and no healthier. Densities of air pollution reach more than six times those considered “highly polluted” by the World Health Organisation.

The city’s traffic has grown increasingly crowded and chaotic for more than a decade, and is a disaster even by the standards of less developed countries (LDCs). Productivity is suffering, as workers with once-short commuting distances now make glacial progress in gridlocked daytime traffic that averages barely five miles an hour. Crowded into dilapidated, steamy, fume-belching private buses, they arrive to work tired, perspiring, short of breath and tainted by dust. Those with cars inch along, tapping their horns their cell phone out and A/C blasting, getting atrocious fuel efficiency. Three-wheeled taxis sometimes jump ahead, but the breezes are short-lived and no healthier. Densities of air pollution reach more than six times those considered “highly polluted” by the World Health Organisation.

You need not be an economist to see that inaction on public transit has become a serious economic drag. A joint study by the Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce and the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport last month pegged lost productivity at nearly Tk 20,000 crore (nearly $3 billion) annually. To estimate the true cost, one would have to factor in the costs of worker demoralisation and the many ailments caused by the extra pollution. You do not need to be an economics degree to say that cutting compressed natural gas filling station hours is a ham-fisted and nonsensical approach to current problems.

This would matter little to economists if there were no better option. But there is: public transport. Just pulling old buses off the road, while well intentioned, does little to ease traffic. Commuters deserve a better option — one that can produce results soon. And it is not enough to have a plan. It must be one that makes economic sense — and the current plan for a “Dhaka underground” or “Metro” does not.

The proposed underground train system, should it come on budget, will cost at least $1.6 billion in its first two-year phrase alone. The odds of it ending up wildly over budget and disrupting traffic for a decade or more are high, given the experience of other countries, even ones with excellent governance records. The dependence on foreign experts (from Japan) will prove costly in the long run. Subways can make sense. They are at least potentially clean and efficient, at least in regions that are not prone to flooding and power outages. But they strain the electric grid, require many years of lead-time before they can be used and involve expensive contracts and feasibility studies.

They are, in fact, too costly even for most wealthy countries’ cities to either start or expand these days. In those trains travel on average for nearly a kilometre between stops — much less means they spending most of the energy stopping and starting — and cost more than Tk 140 ($2) per ride, even when subsidized by the government. So subways are unlikely to pass any rational test in Dhaka for several years. A plan to do the tunnel digging “on the cheap” — to close whole streets, dig down, then cover them back up with scaffolded roadway rather than tunnel professionally — strikes me as a recipe for disaster.

Are there more appropriate, affordable options? Reserved lanes for public buses proved both effective and affordable to many LDC cities, such as Bogotá, Colombia. But those cities were less densely populated, and had citizens that fear traffic police and obey some traffic rules, as well as fewer types of vehicle traffic. Bogotá, for example, had few donkey-pulled carts downtown even a decade ago; mostly it had motorcycles and cars. The same cannot be said of Dhaka. Human-drawn carts and pedestrians, bikes and rickshaws, buses and trucks, three-wheelers, motorcycles and cars all jostle for position with little regard for traffic police, lights or even one-way streets — with impunity. There is only a quarter of the roadway per square kilometre here than in most cities, so that the buses, even newer ones, will still be more efficient at creating pollution than moving people.

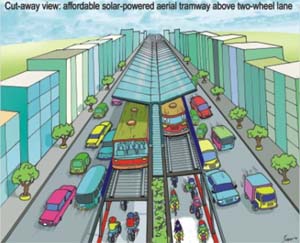

The more appropriate option is an electric tram well above street level, lightweight and riding smoothly on rubber wheels. It could easily sit on struts atop the inside lane of major roadways and cover a full lane that should be reserved for two-wheel bikes and motorbikes. This lane would require barriers and be closed to non-emergency cars and vans, and its entrance should be too low for trucks. Strict law enforcement to keep out rickshaws and CNGs might be needed only at first; but, like drivers in other countries, they could soon learn to respect this law if penalties were similarly stiff. The adjacent lane should be barred to any trucks, due to the potential for damage by collisions to the struts or from loads that often overhang trucks’ sides.

The result would be both increased efficiency and safety below the tram. A cyclist takes up only a sliver of road space and does not pollute; a four-stroke motorcycle pollutes little and uses only sliver more of the road but can also take a passenger. Both forms of commute are ideal, were it not for the danger of other vehicles.

Of course the best time savings would be atop the lane. Even a simple car frame or two could be used as the undercarriage for a lightweight car with room for dozens. The tram could to appeal to well-dressed commuters if kept both clean and free of porters with large loads. (The latter is simply done by using the multi-layered turnstiles that are common in subway systems.) The service might offer a premium fare or a roomier upper deck, with regular checks by tram police. Unlike a rail-based subway, there would be few limits on the frequency of cars.

It would also consume far less electricity. Instead of expending most of its energy starting and stopping the thousands of pounds of each car of a subway train, it would require little more than the power needed to move the weight of its passengers. Simple designs of affordable materials would suffice — aluminum, glass and lacquered bamboo. Such a made-in-Bangladesh solution could be fully rolled out in a few years at a fraction of the cost.

It would respect the density of the city, allowing for more stops. But it should not be all low-tech. Covered with roof of solar panels, it could be a net contributor to the electric grid, pay for itself in less than 15 years while providing rain shelter to the bikes beneath. It would respect the long-term oil and gas shortages, and it would spur growth in a labour-intensive niche of high-tech products now dominated by China. (Bangladesh is already a competitive assembler of such panels.)

Other things would also be needed for this wasteful traffic trend to grow no worse: for example, a freeze on the densification of Dhaka, decently cleared sidewalks and car parking enforcement via towing with car taxes that convince better-off Dhakaites to not buy cars. But people they need realistic alternatives that require bold and smart investment now.

More than 100 years ago, hilly San Francisco was able to build a citywide network of steel rails and wooden trams all pulled by a single looped cable. It still works. And this year, a Chinese firm designed an affordable raised tram big enough to cover two full lanes of buses. Surely Bangladesh, with its own labour and ingenuity, can quickly build an affordable above-road tram in a few years. A system that is cheap and quick to build — and to run — will be viable in the short and long run, and affordable to the mass of city commuters whose patience wears ever thinner.

One that instead uses a costly drain on energy and budgets, complex switching to avoid disastrous accidents, and is vulnerable to weather or unaffordable to the masses is a classic case of foreign corporations skewing the priorities of government officials who rarely set foot in the city’s streets. Perhaps a subway line can be added in future, when it is affordable to the city and the nation. For now, the country can ill-afford to wait, ill-afford the debt, and ill-afford disruption of an inefficient mega-project just so that mandarin can be proud of the big money spent on high-end underground trains for “the people”.

Brendan Weston is an economics teacher and editor from Canada working in Dhaka for an NGO.